So, I’d just like to thank John for inviting me along to speak at the conference today, and when John asked me to come along, he asked me to present a challenging presentation on Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance. I feel I’ve kind of dined out on this a couple of times now, so I thought, “What am I going to do to make this a little bit different?” So, as you’ll see on the slide there, I’ve called it ‘a cautionary tale’. Now this is not a cautionary tale about not using Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance but perhaps more around why you should do it.

So, I’d just like to thank John for inviting me along to speak at the conference today, and when John asked me to come along, he asked me to present a challenging presentation on Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance. I feel I’ve kind of dined out on this a couple of times now, so I thought, “What am I going to do to make this a little bit different?” So, as you’ll see on the slide there, I’ve called it ‘a cautionary tale’. Now this is not a cautionary tale about not using Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance but perhaps more around why you should do it.

So, you need to bear with me here. Once upon a time we had these – now, the sharp-eyed amongst you will have noticed that’s a television set. Well, it was a television set back in the day. That’s probably from around about the late 60s or early 70s. The thing about television sets back in those days was that they were very expensive. They were cutting edge technology of their time. People couldn’t all afford them. And some of you won’t remember a time when everyone didn’t have a television, but there was a time when everyone didn’t have a television, and because they were so expensive, people rented them.

But they were unreliable. And they were unreliable because of this – they were full of these things. Valves. And those who are not so sharp-eyed, but are a little older and have got glasses on, will probably recognise some of these. Thermionic valves – they were full of these things, and because of that they used to heat up, and they were unreliable, they created dry joints, and because they created problems and were unreliable, we needed these. So, this was the TV repairman. And the TV repairman was probably what we could call the television biomed of his day. He was trained in the height of technology; he worked in electronics; he could work out in the field; he would come to your house to fix your rented television. If he couldn’t, he got it in the radio rental van there and he took it back to a workshop looking something like this – which might look a little familiar. People working in the height of technology, heads down, soldering irons out.

So the problem with the televisions back in those days, with them being unreliable, they needed that sort of backup. They needed people who could fix them. And this TV repairman would come to your house and, more often than not, take the back off it, solder something, replace something, and if that didn’t work, he just simply thumped it. That’s probably something I wouldn’t recommend you do with our technology, but that’s how it used to happen.

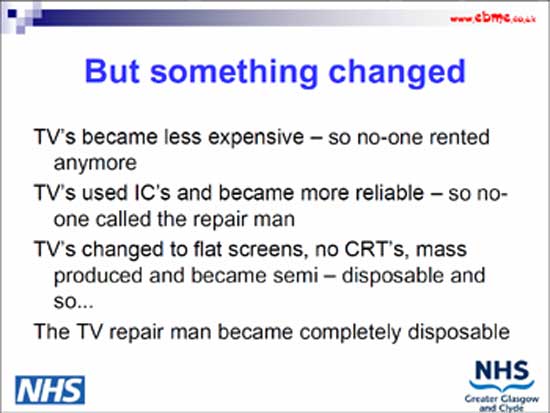

But something changed. TVs became less expensive, so no one rented them any more. They started to use ICs so they became much more reliable, so no one called out TV repairman. TVs became cheaper, semi-disposable, they had flat screens, no CRTs, and therefore the TV repairman became completely disposable. And I have to say that in my 33 years, as John kindly pointed out there, quite a number of TV repairmen came into our game and became biomeds. But the TV repairman as a career disappeared.

So are you seeing a parallel at all here? I’d like you to just think about that. We’ve got an industry which was at the cutting edge of technology; highly skilled technical staff, trained in electronics; but then changes came around. Technology became cheaper, became semi-disposable, had much greater reliability, and it ended up with a whole career now residing in a ‘Where Are They Now?’ file. So I don’t want an answer just now, but think about that. Does anyone think technology might put us out of the game eventually, or certainly change what we have to do?

So, you’re probably thinking, “What’s this got to do with Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance?” Well, I did ask you to bear with me and I would get there. So medical equipment – it’s less costly in relative terms now than it ever was, and a lovely example of this was: in 1989 I moved from Portsmouth up to Glasgow to work in a hospital there, and we got our second pulse oximeter in the whole hospital. And I went into the ITU department who already had one, and at the time they cost nearly £1000 a piece in 1989. You can just think, “Well, that was a lot of money.” So we had two in this entire hospital. Think about how many of those there are now. And then, two years ago, I was in Aldi, and I saw a pulse oximeter for £19.99 in Aldi.

So that tells you something is becoming prolific and is becoming much more accessible, and it’s becoming much cheaper, and it’s much more reliable. It requires less corrective maintenance now that it ever did. And by that, I really mean around technical failures – not disposables, consumables, etc., but proper technical failures. Yet, the stance on service intervals that we get from OEMS or from guidance documents really hasn’t changed. One or two of them have stretched out those intervals, but on the whole it’s pretty much remained stable. You know, this advice that we get. Of course there’s a lot more medical devices now, which is a good thing for us, as you’ll see.

So I think it’s about this: it’s about change and adaption, and securing our profession, looking at, ‘Are we value for money? Are we putting our resources in the right place? Are we managing that risk?’ And it’s still about creating a safe environment for the patient and staff. That’s never changed.

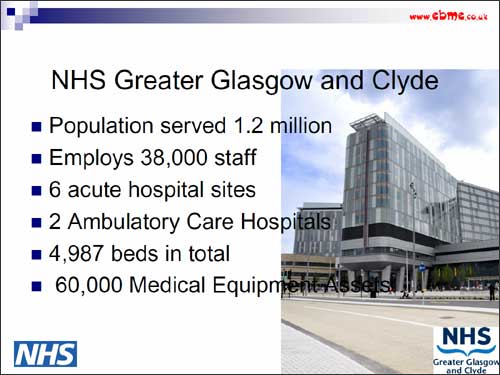

So in order to understand why Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance is really at my heart, I need to just tell you a little bit about me. So, this is about me, here, and my organisation. I work for NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde. We‘ve got a population that we serve of 1.2 million; employ 30,000 staff; we have 6 acute hospital sites; 2 ambulatory care hospitals; and nearly 5000 acute beds and 60,000 assets of medical equipment. And in this picture here, what you see is the Queen Elizabeth hospital. That’s the latest hospital in Scotland that’s been built. Now, that hospital has 14 floors, 1100 beds, a separate 256 bed children’s hospital next to it, and each of these rooms is single occupancy. So, you can imagine that brings with it its own difficulties, and I was just listening about the connectivity and so on – that’s going to become key in the future. So it’s a massive patch that I’ve got to look after.

Now what do I have to actually address that, and what is the advice that I get? Well, you’ve probably already all read Managing Medical Devices 2015 by now, and that’s what they say: “All medical devices and items of medical equipment are to be maintained and serviced in line with the manufacturer’s service manual, and advice from external agencies.” And the CQC doesn’t really say anything really different from that.

Now, I’ll say it from the outset, you might have noticed my accent, and in Scotland we don’t actually have to deal with the CQC so that’s one good bit from my side, but you guys do, and that’s the advice that you get from them. So, in Scotland we have something different – CEL 35, which is another document around actually managing assets.

So this is the advice that we get from the regulatory bodies. What that means to me is I’ve got 49,000 items of equipment that I have to maintain out of those 60,000 that were tested on a regular basis, and most of them, if you follow the regulations – or, sorry, the advice – have got to be tested once a year. I’ve got a total staff complement of 104, of which 78 are designated to tackle that workload, and if I had to comply with what it says in Managing Medical Devices 2015, I would need to employ an extra 26 staff. Do you actually think that if I went to my Chief Executive and said, “I need to employ 26 extra staff,” I would get 26 extra staff? I doubt it very much.

So what did we do? Well, we analysed 30,000 of the assets that we looked after. We put them into risk categories of high, medium, and low, and we took out everything that was life support and said, “Well, we’re not going to look at that.” So we analysed 30,000 assets, 1200 models, and what we found was that the average failure rate – true technical failure rate – was 0.2 failures per annum, so that works out that every five years you’ll get a failure.

We found that – out of the 1200 models – what we found was that only five breached more than one failure in a year. We found that operator error, accessories replacement, damaged leads etc., far outweighed any technical problems. So what we did was we moved away from the recommendations, moved away from the manufacturers advice, and we went to a system of using Risk and Reliability Centered Maintenance, where we had gathered the evidence to show that we could push out those intervals without causing any risk.

Now then, I know what you’re thinking – “Is that leaving you wide open to litigation?” Well, what does the law say? It says, “It shall be the duty of every employer to ensure, so far as is reasonably practicable, the health, safety and welfare at work of all his employees,” and that “the provision and maintenance of plant and systems of work that are, so far as is reasonably practicable, safe and without risks to health.”

So the difference here between the law, which is often termed to be an ass, is that it’s actually coming up with something that’s relatively pragmatic. What it’s doing is it’s setting out an expectation – it’s not actually giving you an edict and saying, “This is what you must do.” It sets out that expectation. And it’s a much more pragmatic approach and I think it’s something that you need to bear in mind.

So while we’re talking about the legal aspects – I’m just going to give a little shout out to my hometown of Paisley in Scotland. So despite the accent, I’m not actually from Glasgow, I’m from Paisley. Now Paisley’s not famous for a whole lot of things. Well, it’s famous I suppose for the Paisley Pattern which a few of you will probably wear from time to time, but it’s actually very famous for a legal case, and the legal case that came from Paisley was one called ‘Donoghue v Stephenson, 1932’. And if you haven’t heard of it, you should really look this up. The reason that I mention this is because this case went all the way to the House of Lords, and a ruling came frpm a Lord Aitken at the time, and that ruling gave us what’s called the Neighbour Principal, or Duty of Care. And that’s a term that you’ll hear in our profession used all the time – Duty of Care. And that came out of this landmark case that said that everyone had a duty of care to their neighbour. And by that neighbour, for us it will be staff, it will be patients, etc., etc.

So the thing about that case is that it gave rise to a term of reasonable foreseeability. So is it reasonably foreseeable that by acting, or omitting something, you could put someone else in the way of harm? And I think if you take that, and you take reasonable practicability, and you put those two terms together, and you look at what you have to do, then you won’t go far wrong, and you certainly will not be stepping outside of the law.

So I think we need some good advice, and the Americans think we need some good advice, and it’ll surprise you to find out that the Americans are actually going to give us some good advice. If you haven’t seen this document before – it’s produced by the AAMI, it’s called EQ89 2015 – then I can thoroughly recommend it. It is the most sensible, pragmatic document that I have ever seen regarding Healthcare Management Technology.

If we just take a look at that first page, you only need to look at the opening statement from these guys, and what they say: ”A maintenance strategy is not a ‘one size fits all’.” So how sensible is that? They talk about expending resources unnecessarily, so that’s the reasonable practicability test. They say consult the OEM procedures, but don’t follow them blindly. They mention evidence, rationale, and consulting with peers – this is marvellous. This is absolutely manna from heaven from us.

They say, consider these things: failure modes and failure effect, evidence of equipment failure, risk, the clinical environment, reliability, performance verification, built in self-testing, mitigation, utilisation, equipment age. They say consider all these things. Doesn’t that sound sensible, and we’re getting this from America – the most litigious society in the whole of the world.

They offer these options – now I don’t pretend to know what some of these actually are, but: corrective maintenance only, planned maintenance, preventative maintenance, predictive maintenance, diagnostic or detective maintenance, and evidence based maintenance. They’re saying you can have these as legitimate strategies for managing your medical equipment. Now, doesn’t that seem sensible? It’s not a ‘one size fits all’; it shouldn’t be ‘do as you’re told’; it should be around what you can do with the resources that you’ve got.

So I think that what you need to do is you need to think about the future. You need to consider the technological advances and what their impact might be, including reliability and risk, because things won’t always be the same. We’re already hearing from John this morning about some changes that are coming – AI – things will not always be the same. Think about maintenance strategies that will balance your risk and your resources, and think carefully about how you use your valuable resources, because I think that that may well come up later on when we’re debating around bringing contracts and things out in house, and where you’re going to get that resource from.

So, lastly, think about what you do. Releasing time to do this other work I think will be come much more important in terms of value for money, and let’s face it, we’re all under the same stresses and strains. I was talking to someone last night from the commercial sector – they have targets to meet and it’s around making money; we’ve got targets to meet and it’s around saving money. It’s just two different ends of the spectrum. Now, reliability seems to be taking care of itself, or the manufacturers are taking care of that for us, because they’re making the equipment much more reliable than it ever was. So we need to think then about how we react to that, and how we use that resource, and how we manage that time.

You need to manage the risk. There isn’t any doubt about that – you have to manage that risk. There is a baseline that you can’t go below which is set out by the Health and Safety at Work Act. You are going to have to do something, but you need to think about what it is you do, how often you do it, and what skill levels you actually allow to do that work. These things are going to be very important for the future, because there’s not going to be any more money and times are going to get tougher.

So you need to manage that risk, and don’t over-maintain the equipment. Don’t just keep doing what you’ve always done because you have to, or you think you have to, and that’s the way you’ve always done it. And you’ve got to use your resources much more wisely, and I think you have to think, “Well, do we want to end up like the TV repairmen, where technology gets ahead of us?” It becomes so reliable; it becomes interconnected; it becomes able to be interrogated and maintained remotely, which would mean less staff. You need to think about where you want to go with this, and where our profession is going to go with this.

And I thank you all for listening to me, and I’d be happy to take any questions. And I hope that’s provoked you a little bit.

Ted Mullen's presentation at the EBME Seminar, may be downloaded here: http://www.ebme.co.uk/downloads/category/17-2016-seminar